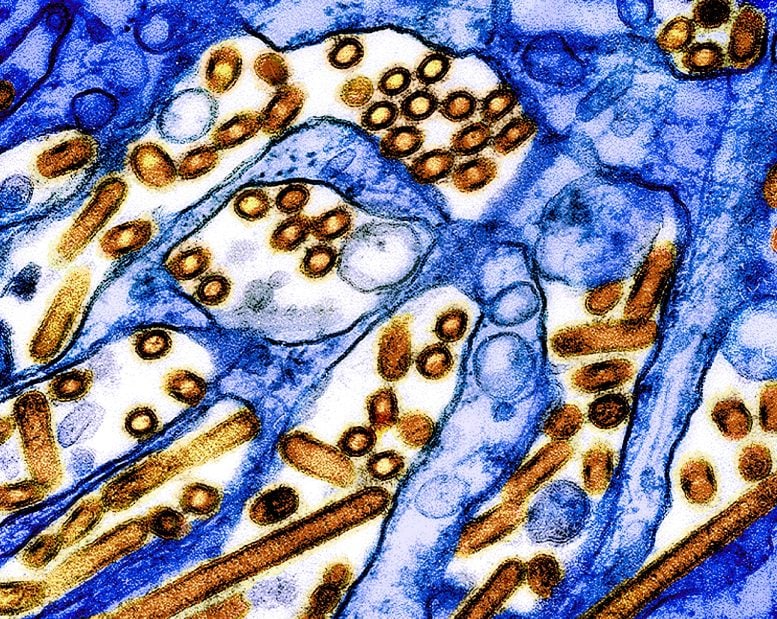

A cow rests in her stall. In the foreground is a colorized transmission electron micrograph of H5N1 virus particles (yellow). In 2024, H5N1 avian influenza caused outbreaks in poultry and U.S. dairy cows. Cow photo by NIAID; micrograph, which has been relocated and recolored by NIAID, is courtesy of CDC. Credit: NIAID and CDC

Research into H5N1 influenza in US dairy cattle shows that virus can cause severe disease in mice and ferrets, but lacks efficient transmission via respiratory droplets. This finding suggests limited potential for these bovine-derived viruses to cause widespread disease in mammals.

Experimental findings of H5N1 infection in US dairy cattle

A series of experiments using highly pathogenic H5N1 avian influenza viruses (HPAI H5N1) circulating in infected U.S. dairy cattle showed that viruses from milking dairy cattle caused severe disease in mice and ferrets when administered via intranasal inoculation. Virus from H5N1-infected cows bound to both avian (bird) and human cellular receptors but, importantly, was not efficiently transmitted between ferrets exposed via respiratory droplets.

The findings, published July 8 in the journal Naturesuggest that bovine (cow) HPAI H5N1 viruses may differ from previous HPAI H5N1 viruses and that these viruses may possess characteristics that facilitate infection and transmission between mammals. However, they do not currently appear to be capable of efficient respiratory transmission between animals or humans.

In March 2024, an outbreak of HPAI H5N1 was reported in U.S. dairy cattle, spreading through herds and resulting in fatal infections in some cats on affected farms, spillover into poultry, and four reported infections among dairy farmers. The HPAI H5N1 viruses isolated from affected cattle are closely related to H5N1 viruses that have been circulating among wild birds in North America since late 2021. Over time, those avian viruses have undergone genetic changes and spread across the continent, resulting in outbreaks in wild birds and mammals, sometimes with fatalities and suspected intra-avian transmission. kind.

Colored transmission electron micrograph of avian influenza A H5N1 virus particles (yellow/red) grown in Madin-Darby Canine Kidney (MDCK) epithelial cells. Microscopy by CDC; repositioned and restained by NIAID. Credit: CDC and NIAID

Research methods and results of animal models

To better understand the characteristics of bovine H5N1 viruses, researchers from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, Japan’s Shizuoka and Tokyo Universities, and the Texas A&M Veterinary Medical Diagnostic Laboratory conducted experiments to determine the ability of bovine HPAI H5N1 to replicate and cause disease in mice and ferrets, which are routinely used for influenza A virus studies. Ferrets are considered a good model for understanding potential influenza transmission patterns in humans because they share similar clinical signs, immune responses, and respiratory infections as humans.

The researchers administered intranasally increasing strength doses of bovine HPAI H5N1 influenza to mice (5 mice per dosing group) and then monitored the animals for 15 days for changes in body weight and survival. All mice given the higher doses died from the infection. Some mice given the lower doses survived, and those given the lowest dose experienced no weight loss and survived.

Comparative studies and transmission tests

The researchers also compared the effects of the bovine HPAI H5N1 virus with a Vietnamese H5N1 strain typical of the H5N1 avian influenza virus in humans and with an H1N1 influenza virus, both administered intranasally to mice. The mice given either the bovine HPAI H5N1 virus or the Vietnamese avian H5N1 virus showed high levels of virus in respiratory and non-respiratory organs, including mammary glands and muscle tissues, and sporadic detection in the eyes. The H1N1 virus was only detected in the animals’ respiratory tissues.

Ferrets infected intranasally with the bovine HPAI H5N1 virus experienced elevated temperatures and weight loss. As with the mice, the scientists found high levels of the virus in the upper and lower respiratory tracts and other organs of the ferrets. Unlike the mice, however, no virus was found in the ferrets’ blood or muscle tissue.

“Our pathogenicity studies in mice and ferrets together demonstrated that HPAI H5N1 from lactating dairy cattle can cause severe disease following oral ingestion or respiratory infection, and infection via the oral or respiratory route can lead to systemic spread of virus to non-respiratory tissues, including the eye, mammary gland, nipple, and/or muscle,” the authors write.

To test whether bovine H5N1 viruses are transmitted between mammals via respiratory droplets, such as those expelled by coughing and sneezing, researchers infected groups of ferrets (four animals per group) with either bovine HPAI H5N1 virus or H1N1 influenza, which are known to be efficiently transmitted via respiratory droplets. One day later, uninfected ferrets were housed in cages next to the infected animals. Ferrets infected with either influenza virus showed clinical signs of illness and high levels of virus in nasal swabs collected over several days. However, only ferrets exposed to the H1N1-infected group showed signs of clinical illness, indicating that bovine influenza virus is not efficiently transmitted via respiratory droplets in ferrets.

Normally, avian and human influenza A viruses do not attach to the same receptors on cell surfaces to initiate infection. However, the researchers found that the bovine HPAI H5N1 viruses can bind to both, raising the possibility that the virus can bind to cells in the upper respiratory tract of humans.

“Collectively, our study demonstrates that bovine H5N1 viruses may differ from previously circulating HPAI H5N1 viruses in possessing a dual human/avian receptor binding specificity with limited transmission via respiratory droplets in ferrets,” the authors said.

Reference: “Pathogenicity and Transmissibility of Bovine H5N1 Influenza Virus” by Amie J. Eisfeld, Asim Biswas, Lizheng Guan, Chunyang Gu, Tadashi Maemura, Sanja Trifkovic, Tong Wang, Lavanya Babujee, Randall Dahn, Peter J. Halfmann, Tera Barnhardt, Gabriele Neumann, Yasuo Suzuki, Alexis Thompson, Amy K. Swinford, Kiril M. Dimitrov, Keith Poulsen, and Yoshihiro Kawaoka, July 8, 2024, Nature.

DOI file: 10.1038/s41586-024-07766-6

The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), part of the National Institutes of Healthfunded the work of researchers at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.